The art of cat handling for films has been around for quite some time, but rarely do we get to see a glimpse of the craft documented in the media covering Hollywood in its heyday. But such was the case for cat handler Walter Huber, who was interviewed about his work in bringing the cat character “Cleopatra” to life in the 1947 film Cass Timberlane.

One of the earliest reports about the casting of Cleo came in a column called Hollywood Film Shop by Patricia Clary published in The Republic on June 18, 1947:

‘Cattiest’ Player.

One thousand candidates were examined before Hollywood’s “cattiest” player was chosen.

To fill a top role in one of Hollywood’s top pictures, she had to be attractive, aloof yet responsive, pliable but dignified, athletic yet pussy-footed, sophisticated in a feline way, and for all that, kittenish.

Cleo is.

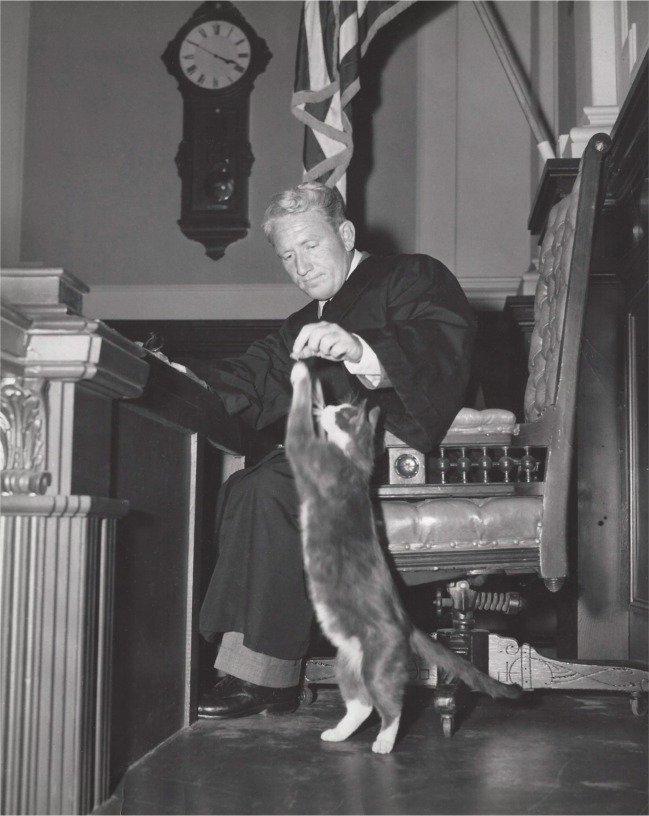

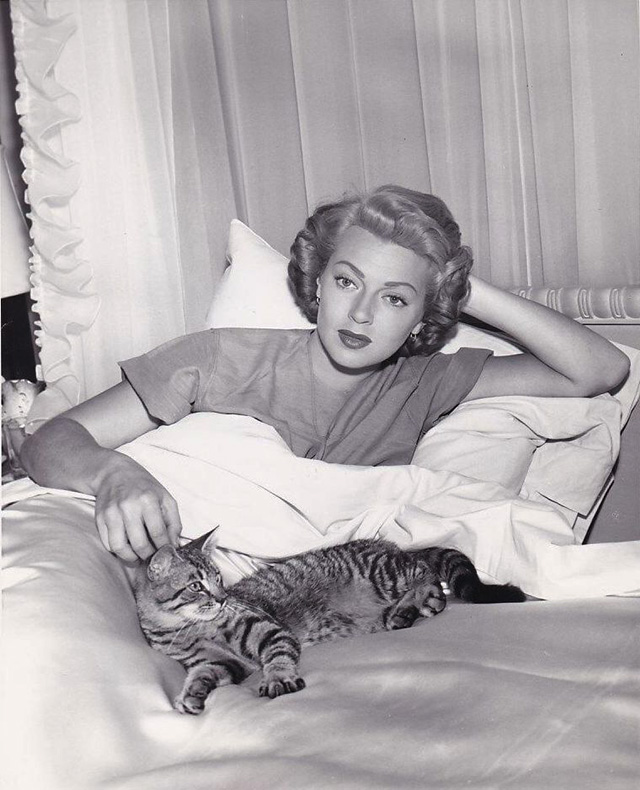

She’s the 4-footed charmer of “Cass Timberlane,” the cat that is the bane of Spencer Tracy’s life and the solace of Lana Turner’s. Cleo, incidentally, has equal screen footage with the stars.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s search for the important performer started with William W. Huber, Hollywood’s cat specialist who has supplied the screen with felines for 20 years. Despite his menage (sic) of 25 cats, Huber didn’t have one to fit Cleo’s description.

“They were too common,” a studio official explained. “Cleo is the kind of cat who never forgets she’s a lady.”

1,000 Cats Viewed.

Huber sent an SOS to the SPCA, which unlatched its cages and hustled together 1,000 cats. Cleo was one of them.

She got a 4-week course in acting, along with treats of liver and thin cream seasoned with catnip.

“Not too much,” Huber said. “Catnip is to cats what alcohol is to humans. Cleo loves it.”

Cats, as movie actors, can’t be hurried, are independent of direction and so a scene just as they please.

In private life, Huber confided, Cleo isn’t the perfect lady she will appear on screen.

Hollywood’s cattiest player really answers to the name of Willlie. He’s no lady at all.

The above article obviously took some liberties with the facts, making it sound as if Cleo was played by just one cat actor. A later article, penned by an unknown author and appearing in The Milwaukee Journal on December 2, 1947, painted a more realistic picture:

Cats Stubborn, Unpredictable, Says Movie Feline Expert

Hollywood, Calif. — Eight homeless cats of the alley variety, which were obtained from the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, are the latest screen arrivals to lend proof to Hollywood’s accepted theory that the greatest scene stealers in pictures are children and animals. Of the eight selected for film careers, six of the larcenous felines were required to portray Spencer Tracy’s sneeze impelling house pet, Cleo, in “Cass Timberlane.” The other less-fortunate two merely play themselves in minor roles, appear briefly, and were no problem to cast.

Why it took six cats to portray what should be a simple role to an everyday tabby and what went on behind the scenes to get the one in six Cleos to respond to direction and at times compete for footage with Tracy and Lana Turner, is an interesting side light which involves Hollywood’s animal providing and taming industry and particularly Walter Huber, a 54 year old ex-printer who finds cats more profitable than type.

Cat Specialist

As Huber explains, it was simple for Author (Sinclair) Lewis to write catlike antics for his Cleo in the novel and it was equally as easy for the scenarist to transfer such imaginative frolics to the screen play, but getting a cat to follow script — well, that’s where Huber comes into the picture. It would have been some other animal specialist, he points out, had Cleo been a monkey, a dog, a crow, a horned toad, or some other bird or beast.

Hollywood has its specialists for every type of animal, bird or reptile likely to be called for a movie part. These specialists have their own protective organization with a set of ethical standards, minimum rate scale for their own services, and “salaries” for their stock in trade depending on rarity, extent of training and — of course — “name” value. One advertises he can supply anything from an ant to an elephant.

It isn’t unusual for the salary of the animal engaged to be higher than that of its owner, or handler, who works through the production of the picture with it. Take the case of Lassie, for instance. He’s a star and recognized as such on MGM’s star roster along with the Gables, the Garsons and the Hepburns.

In the case of Huber, the cat expert — and this is the commonest procedure at the studio where animals are involved — he was hired as “cat trainer” for the full run of the production of “Cass Timberlane.” In addition, the feline actress or actor which he would supply and train to play Cleo would receive a salary of $100 a week for the same length of time. But when Huber was engaged for the stint, several weeks before the start of the film, there was no Cleo in sight — in fact, some of the cat actors that filled the role in the picture were not then born.

Cats Are Unpredictable

The script called for a tabby of the alley cat type which is first seen as a kitten, several weeks old; later is filmed in antics as a cat of around 4 months old, and in a subsequent sequence as a 1 year old. That meant three different cats at approximately those ages which must, for camera purposes, be look-alikes. But as cats are somewhat on the independent and unpredictable side, Huber’s task included also the finding of three additional look-alikes of those ages to understudy the originals.

To find his cats, Huber turned to the Los Angeles SPCA, where unwanted animals are left by their owners for possible sale or, what is a more likely, fate for pussies of the alley category — humane destruction. Before Huber finally got his six look-alikes of the varying ages, it meant for him many daily trips to the SPCA. But he did get them and thus saved six cats, or 54 lives, for Hollywood fame. Only two of the half dozen were relatives, brothers — and all were male.

There was not much time to train the youngest pair for their screen career, as they were before cameras within a few weeks of their birth and they would be expected only to look kittenish anyway. For the older couples which would have to “act,” it meant many hours of training by Huber to teach the cats to answer to signals.

Not Much Competition

Despite their training it still took more tedious hours to get them to do the right thing at the right time for the camera. “Cats are so obstinate,” says Huber, “they will not do anything unless they have satisfied themselves there is a reason for it. It’s much easier with dogs. That’s why I’m in the cat business. There are too many dog men, but there’s not so much competition in cat handling.”

For “Cass Timberlane” the most tedious cat routine to get for the cameras, according to Huber, was the comedy high light scene in which Tracy turns from the radio, makes a face at Cleo and says, “I’m a green monster,” and the cat looks for a moment in apparent amazement at the actor’s grimaces and then turns tail and runs across the room and up a flight of stairs, without halting.

“It wasn’t so difficult, after all, to accomplish,” says Huber, “but it did take two cats to do the scene. One of them ran away from Tracy, as per direction, but would only go part way up the stairway and then stop, turn around and start down again. Shot after shot was taken and each time the cat would stop midway and turn as if thoroughly disgusted with the whole affair.

One For All

“So a scene was taken in which the cat’s brother starts at the bottom of the stairs and scoots all the way up and off stage. Then with a bit of camera doubling it appears to audiences as if there is only one cat involved in this funny one shot incident.”

Huber believes that, as a result of the performances of the collective Cleo in “Cass Timberlane,” he now has a new feline star on his hands. But just which one of the six he considers the star actor and which are the understudies, he isn’t saying. “From here on out,” he declares, “Cleo works only as a team of six — one star, five doubles, one for all and all for one.”

Further quotes from Huber about his work on the picture appeared in print as such:

“Huber writes that cats, unlike dogs, seldom forget their dignity . . . they can’t be hurried, are independent and usually do what they want to. Each cat is an individual with a different disposition. Like women, according to Huber, they’re fickle. Cats take their color from their surroundings. It’s environment, not heredity, that counts with them. A cat that lives with an old maid eventually acts like an old maid, but Huber is too smart to say that the reverse is true.”

And finally an article appeared in the December 6th, 1947 edition of The Charlotte News. Written by Emery Wister, who reported on the film and its feline stars this way:

There was a dandy catfight on MGM’s stage 8 where Spencer Tracy and Lana Turner were up to their necks in a scene of “Cass Timberlane.”

No offense, Lana, the fight was between two felines of the four footed variety and the meows, screeches and hisses could be heard from here to yonder.

The cats were only two of eight, cast in the film. Six played Tracy’s cat, Cleo, and the other two had bit roles as neighborhood prowlers. And let me tell you that Lana and Mr. Tracy had to be up on their tricks to keep the kittens from walking off with every scene they were in.

The character of Cleo made an impression both in the original book and on screen. So much so that the band Benton Harbor Lunchbox wrote a song about her which you can listen to on their official Bandcamp Page.

Click here to read our review of Cass Timberlane.

To discuss this feature story and other cats in movies and on television, join us on Facebook and Twitter.